What is an entrepreneurial society? I think of it as a socio-economic system that is capable of constantly renewing itself. It retains its identity by constantly recycling and restructuring its elements. It achieves that elusive quality that Peter Drucker looked for in organizations throughout his career – a “balance” between continuity and change, order and movement.

For basic illustrations one can turn to nature. Ecosystems like temperate forests offer an example that may be paradigmatic; the innovative process begins in an open patch, where there is equal access to sun and rain and space for small-scale experimentation. We call the pioneers that come into this patch “weeds” – fast-moving organisms with simple structures, suited to exploring every nook and cranny. Funded by the local seed-bank and augmented by resources that drift in from afar, everything grows rapidly with little competition. Over time however, as the patch becomes crowded and competition for resources increases, larger organisms will start to gain a foothold; these “shrubs” may not be as agile as the weeds they replace but they have a capacity to harvest resources more efficiently. With deeper roots and longer stems they can get to the water and sun first. As they flourish they shade their rivals. The forest starts to grow up as the economies of scale begin to exert their effects on the system. Eventually large hierarchies – tall trees – will take over the patch. They are very efficient in their use of resources but their dense canopy will block the sun and their deep roots will hog the water, allowing little to grow beneath them. The system is now impressively large but it is a mature monoculture with apparently little capacity to renew itself.

Ecological renewal takes place via nature’s forces of destruction: wind, fire, flood and pestilence. These processes continually test the system, break down the decadent growth, recycle its components and open up the opportunity spaces into which pioneers can come. The cycle is now ready to repeat itself – think of a Moebius strip with long processes of growth on the “front” (left to right) S-curve and rapid processes of destruction on the “back” (right to left) reverse S-curve. Such a system maintains what seems to be a steady state through constant change: or, as the French say, plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose (the more things change, the more they stay the same).

So much for the illustration, but do we observe similar dynamics in human systems? I think that we do, once we have made adjustments for the fact that we are dealing with human beings rather than trees. From an ecological perspective human enterprises are conceived in passion, born in communities of trust, grow through the application of reason and mature in power. Here, like a forest of mature trees, they tend to get stuck, which sets them up for crisis and destruction, but with the possibility of renewal. From this perspective both capitalism and democracy are best viewed as ecosystems of ecosystems that allow societies to retain their identity while constantly recycling and restructuring their elements. One would expect them too to traverse a Moebius-like path as they go through the complex process.

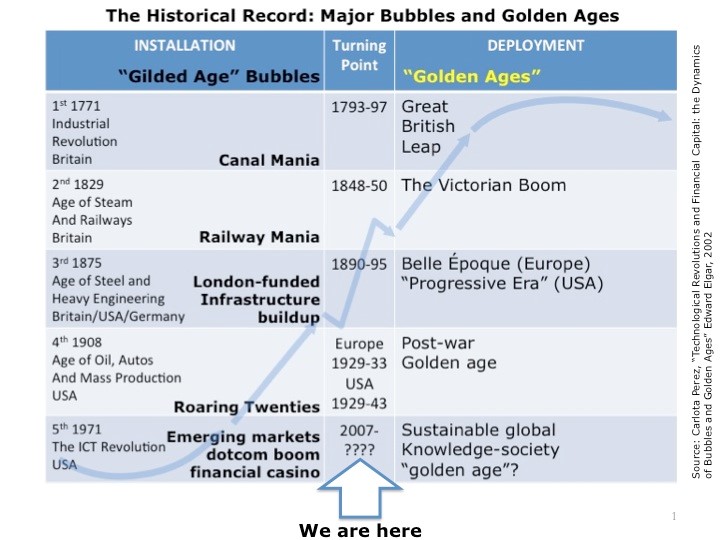

The work of Neo-Schumpeterian economist Carlota Perez highlights the front S-curve of the Moebius strip as it applies to technological innovation. She has identified five technological revolutions since the 18th Century (see diagram).

Each curve features an early installation phase with radical innovations funded by capital made idle by the exhaustion of the previous cycle. New technologies irrupt into the social system, disrupting industries and creating all kinds of new tensions. These technologies make some skills obsolete and others valuable. Typically the installation phase ends in a “Gilded Age” financial bubble, as speculation (and the building of infrastructure) runs ahead of the capacity of the new innovations to deliver sustainable returns. What follows is an interregnum (Turning Point), a period of adjustment as the new technologies begin to penetrate every aspect of society. During this turn the focus of finance turns from speculation to financing developments in the real economy, from a laissez-faire attitude to a more directed effort to harness technology for the betterment of society. In the past this has lead to “Golden Ages”.

Perez suggests that we are currently in the transition between the installation and deployments phases of the Information and Telecommunications revolution that began in the USA in the early 1970s. She adds that a successful transition will not happen by itself – a set of policies is needed to tilt the playing field firmly away from the casino economy to the real economy and promote its conversion to a Green Economy. This will be the 21st Century counterpart to the urban reconstruction and suburbanization that followed in the aftermath of World War II. The policies will be complex mixes of sticks, carrots and education.

In Landmarks of Tomorrow (1959) Peter Drucker described the Western world’s fundamental habit of thought as “Cartesian”. This is our tendency to approach the world as detached, objective observers. We see reality as consisting of enduring objects “out there”. This is not a neutral perspective; it comes with a deep bias that regards what is stable as “good” and what is changeable as “bad”. A Cartesian view of reality isn’t wrong: it has been hugely successful when applied to the physical world and making social systems more efficient. But it isn’t adequate to deal with innovation and the tangle of tensions and uncertainties in the complex challenges we now face. It asks the wrong questions and its view of causation is too simple. An ecological/systems perspective poses different issues. It asks us to consider the relative rates of destruction and creation in society and the scales of the new technologies compared with those they are replacing. It sensitizes us to the environments – the “open patches” – that nurture entrepreneurship and to the institutional arrangements that can deter it. We become aware of the tax and fiscal climate – the policies that spur certain dynamics and curb others – and the development processes that cycle and recycle the system’s resources.

Once we can see enterprises and institutions as movements rather than just structures, our minds turn from mainstream economics, with its equilibrium assumptions, to a reconsideration of alternative economic canons of disequilibrium – Schumpeter, Boulding, Minsky and others. We begin to see social science, not as the application of theory to practice, but as a form of practical wisdom – the disciplining of reflections arising from experience. It becomes clear that managing an organization can never be a purely rational, Cartesian exercise. Much is context-dependent and we have to understand the genealogies of social institutions, their norms and their values and their dynamics of power and dominance. We need a new sensitivity to our language and the mental models embedded in the images and metaphors we use. As systems scientist Ross Ashby pointed out many years ago, we require mental models as least as complex as the phenomena we are trying to understand and influence. Once we have this facility to play with many different perspectives in many fields, perhaps we will have a truly entrepreneurial society.

About the author:

David K. Hurst is a management author, educator, and consultant. His latest book is The New Ecology of Leadership: Business Mastery in a Chaotic World (Columbia University Press 2012).