Hate speech to the extent we see it today has surfaced recently. Populist and right-wing protest voters could have voted as they did of late 10 or 20 years ago. They didn’t. How could such destructive resentment build up? Opinion polls may not prove overly helpful in diagnosing the underlying reasons as they are typically influenced by narratives circulated by real or fake news sites, but hardly any substantiated reasoning. A recent study set out to shed some light on causation and help answer the pressing question: How did we get here?

Self-inflicted misery: Death by fiscal policy

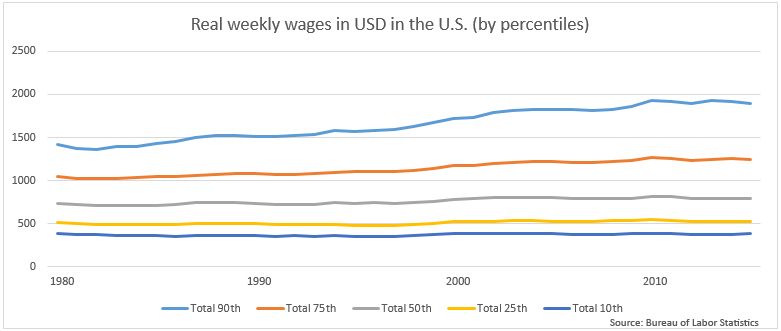

The first indication that the recent growth in populist votes may have something to do with the economic outlook of voters reveals itself via the geographical distribution of voting results. GDP per capita shows that on average wealth is growing. If we were to look at what arrives on average employee’s pockets instead the time series of real wages show a different picture: In the US the bottom 50 percent of the working population have had no real wage increase since at least 1979.

In the UK, real wages overall were 7 percent lower in 2015 than in 2000 (compared to +7 percent for Canada over that period). Simply demanding employers to increase gross wages might not solve the problem, as tax policy heavily influences the net. In some countries, gross wages went up while net real salaries dropped. The connection between real wages and votes as indicated in our long-term study seems to explain why – in contrast to many long-established governments – President Erdogan sees endured support: Turkey’s real wages are up 40 percent in the past 10 years. Simply put, voters’ preference for economic betterment outweighs reasons to change established norms.

First results of these analyses, published in early 2016, showed a strong link between weakened real wages and anti-government votes. The strong link between real wages and election results quickly dawned on policy makers: a quiet turn of fiscal policy, away from austerity and with an ease on lower incomes, was announced by September 2016.

Recommendation: Governments seem to be voted in or out not by their ideology but by their ability to deliver better living standards. Regressive taxation tends to increase inequality and seems to lead to prolonged periods of stagnation by causing risk-taking and engagement to reduce as effort does not pay off anymore. The result is what nobody wants: low growth for everyone and social unrest building. Inclusive policies, on the other hand, balance fiscal burdens well between high and low incomes and prevent tax leakage. As such, they create opportunity for individuals and on businesses to grow through effort, which spurs engagement and in turn creates sustained growth and social peace (as demonstrated in Why Nations Fail). Countries can engage in fruitless confrontation over inequality or choose to invest the same time and energy into generating wealth for everyone. In other words: legislation can create wealth and equality – or reduce it. Growth, prosperity, equality and inclusivity versus stagnation and inequality: that is the choice.

Are we looking at the right indicators?

The late Hans Rosling never tired of explaining that fewer people than ever live in poverty and that the world sees a permanent increase in GDP per capita. Max Roser, a researcher at the University of Oxford is on a similar mission with OurWorldinData.org – promoting data-based understanding and knowledge. However, several recent election results and the Brexit referendum suggest that many seem to disagree that we’re all better off.

The one undisputed perception is that GDP does not serve well as an indicator of growth and prosperity. More telling could be the long-term development of real wages, broken down in percentiles, which helps judge better the distribution of incomes.

Communication must change

An increasingly hatefilled public discourse reveals an alarming account of disintegration of society. Stigmatizing Leave voters in the UK or Trump voters in the US (and similarly in other countries) as dumb, uneducated, too old, or simply as “globalization losers,” and using a vocabulary of disgust against populism and hate speech must be counterproductive. Resentment will only increase. On the other hand: Communication alone, even if undertaken with great care, without fixing root causes of inequality, remains ineffective in the long run.

More proof from the inclusive policy “toolset”: Participation and Collaboration

Studies show that policies are endorsed better by those who participated in their creation or implementation than by those who were not involved. If governments want endorsement and trust then participation seems to be the way forward.

The CEO of Wikifolio has explained that members on his platform publish their trading strategies and that the portfolios quickly outperformed his country’s Stock Exchange in trading volumes. He was asked: “Why do people do this?” Here the research of Alexander Pentland (MIT) comes in: Lone Traders generate the lowest returns, the ones with publicly discussed trading strategies see the highest yield. Pentland looked at a number of other fields, with the same result. Also, he estimated the gross urban product of cities with little deviation based on indicators drawn from these findings. It can be summarized as: the more collaboration, interdisciplinarity, openness and mingling, the more wealth.

Towards Growth and Inclusive Prosperity

Policy and public discourse require a set of new values, indicators and vocabulary. The authors of Why Nations Fail collected evidence on what makes nations successful: Inclusive, pluralistic societies, where social advancement can be achieved through engagement and risk-taking. Extractive systems, on the other hand, withdraw resources from society and deliver benefits for a small upper class only. Consequently, engagement dies and converts into bitterness once individuals cannot achieve adequate income through work.

Conclusion: Extractive systems degenerate, inclusive systems prosper. If growth is what we are after then inclusive concepts are the way forward.

Concepts from the authors new book, Government of Hope, to be published in 2018

Isabella Mader is CEO of the Excellence Institute lectures at several universities. Her background is in Information Science and Business Administration and in. 2013 she was “Top CIO of the Year”. Her current research focusses on Network Economy and Collaboration.

Wolfgang Müller is Deputy Chief Executive Director and Chief Operations Officer of the Vienna City Administration. He holds a Masters degree in Law and a Master in Business Administration.

The opinions and views expressed in this article are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those of the institutions to which they are affiliated.