The humanist strand of management thinking that celebrates teams and collaboration through respect for customers and workers as human beings has a long and distinguished history. It includes Mary Parker Follett (1920s), Elton Mayo and Chester Barnard (1930s), Abraham Maslow (1940s), Douglas McGregor (1960s), Peter Drucker (1970s), Peters and Waterman (1980s), Katzenbach and Smith (1990s), and Gary Hamel (2000s).

Yet despite almost a century of fine management writing and many successful initiatives, the ugly truth is that the lasting impact on general management practice has been limited. Even humanist change initiatives that were dramatically successful by objectively measured standards have often been discarded by the firms that introduced them. Sooner or later, firms revert to stultifying bureaucratic practices, as if on some zombie-like automatic pilot.

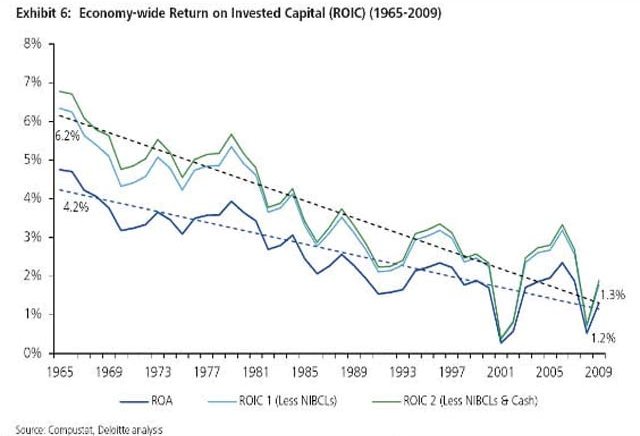

Many large publicly-owned corporations continue to implement hierarchical bureaucracy and, since the 1980s, pursue the goal of maximizing shareholder value as reflected in the stock price, despite steadily declining returns on assets and on invested capital. The problem is not so much excessive focus on quantitative metrics or technocratic logic, but rather failure to respond to obvious quantitative truths staring managers in the face.

Achieving humanistic management has thus turned out to be a much more intractable problem than most thought leaders expected it to be. Instead of management comprising linear mechanisms that could be improved one-by-one through implementing proven remedial measures, it has acted more like an ingeniously morphing virus that steadily adapts itself to, and ultimately defeats, intended fixes and returns to its original state, sometimes more virulent than before.

Why is change so difficult? One reason is that an unholy alliance links shareholder value theory and hierarchical bureaucracy. Once a firm embraces maximizing shareholder value and the current stock price as its goal, and lavishly compensates top management to that end, the C-suite has little choice but to deploy command-and-control management. That’s because making money for shareholders and the C-suite is inherently uninspiring to employees. The C-suite must compel employees to obey. The result is that only one in five employees is fully engaged in his or her work, and even fewer are passionate. The very foundations of humanist management—collaboration and trust—are missing.

The good news is that the Internet is now forcing change, by:

- Shifting power in the marketplace from seller to buyer. Customers, who have access to reliable information about the available choices and a capacity to interact with other customers, are now collectively in charge.

- Raising customers’ expectations. As “better, cheaper, faster, smaller, more convenient, and more personalized” became the new norm, the ability to innovate with committed employees became critical.

- Requiring firms to draw on the passion and full talents of those doing the work to find ways to delight customers.

- Shredding vertical supply chains, as customers can buy a wider array of stuff online cheaper, and often quicker, than in a physical store.

- Spawning vast new horizontal value chains, in which millions of people began creating their own virtual meeting places and marketplaces with their own lateral economies of scale.

- Enabling firms to create huge ecosystems of contractors and customers that can achieve scale without the sclerosis of hierarchical bureaucracy.

These shifts require not just increased attention to customers by strengthening the marketing department or introducing rah-rah employee engagement programs. They require rethinking the fundamentals of management.

The foundation is Peter Drucker’s insight of 1973: the only valid purpose of a firm is to create a customer. It’s through providing value to customers that firms justify their existence. Profits and share price increases are the result, not the goal of a firm’s activities.[1]

The locus of competitive advantage is now determined by interactions with the customer, built on the work of engaged and passionate workers. The central strategic questions of the industrial model, “How much more can we sell?” and “How much money can we make?” are replaced by “Why should customers buy from us,” and “What else do customers need?”

As Ranjay Gulati notes in Reorganize for Resilience (2010), it means orienting everyone to the goal of delivering more value to customers sooner, and aligning all decision-making with this goal. It is a shift in mindset from “You take what we make,” to “We seek to understand your problems and will surprise you by solving them.”

While armies of dispirited bureaucrats, driven by command-and-control, simply can’t get this job done, the enabling management practices and metrics of humanistic management are well suited to it. When the goal is the inherently inspiring goal of delighting customers, managers don’t need to make employees do their job. With managers and workers sharing the same goal—delighting customers—the humanistic management practices of trust and collaboration become not only possible but necessary.

To be sure, other changes wrought by the Internet bring new challenges that must also be dealt with. Increasing income inequality must be addressed with more progressive tax policy. Excessive financialization of the economy must be resolved by reining in the financial sector. Abuses of burgeoning monopolies must be met with stronger anti-trust action. Threats to privacy must be averted by appropriate regulation. The rights of vast numbers of part-time workers and “permatemps” must be protected through appropriate legislation. Education systems must support greater entrepreneurial skills and life-long learning to prepare people for the new world of work. Greater support must be provided for individuals to start their own businesses.

But the most important battle in the war for humanistic management—compelling firms to respect customers and employees as human beings—has already been won. The choice for organizations today is: change or die.

About the author:

Stephen Denning is the author of The Leader’s Guide to Radical Management (Jossey-Bass, 2010), which describes management principles and practices for reinventing management to promote continuous innovation and adaptation. Over 600 of his essays on these themes are available at: http://blogs.forbes.com/stevedenning/.

[1] Drucker, P. Management: Tasks, Responsibilities and Practices, Heinemann, 1973.