Strong, horizontal work practices go beyond the empowerment of individuals and teams.

The entrepreneurial work culture is one of experimentation, creativity, and risk-taking in the belief that the outcome will be beneficial. Experimentation and creativity have long been stifled in many organizations. Command-and-control leadership, overly complex processes and slow decision-making are among the reasons for this unfortunate state. Data from my 10th annual research with 310 participants in 27 countries confirm this: 47% say their C-level managers have command-and-control leadership styles, 53% say their organizations have complicated processes, and 40% say slow decision-making is a serious concern holding back transformation initiatives.

Only 37% agree that people freely challenge ideas, including the business model and work practices. How can people be engaged, giving their most and enjoying life in these organizations? It is unlikely that new ideas will be born, developed and delivered in such environments.

In the economic and social environment today where business leaders are concerned about new competition, changing customer demands and even long-term survival, it is time to pose a fundamental question. How can organizations create work cultures where motivated people produce new ideas and work with a passion for achieving them? In other words, how can you trigger and sustain an entrepreneurial-friendly culture?

Some companies are injecting entrepreneurship into their businesses by creating incubators where small, nimble teams, isolated from the rest of the organization, do “lean innovation.” These initiatives, positive as they are, do not address the fundamental question of how established organizations can build an entrepreneurial mindset, learn to experiment and create new value for customers.

In my research, I asked respondents to indicate their agreement with the statement: “We have a work culture of freedom to experiment and take initiatives.” Only 15 organizations strongly agreed with the statement, and, interestingly, the organizations are very different. They range in size from under 500 to over 100,000 employees and are based in Europe, North America, and Australia. They work in different sectors including consumer retail, banking, food and agriculture, government, humanitarian, construction and professional services.

The demographics are extremely diverse, but work practices are highly similar across the organizations in this entrepreneurial sample.

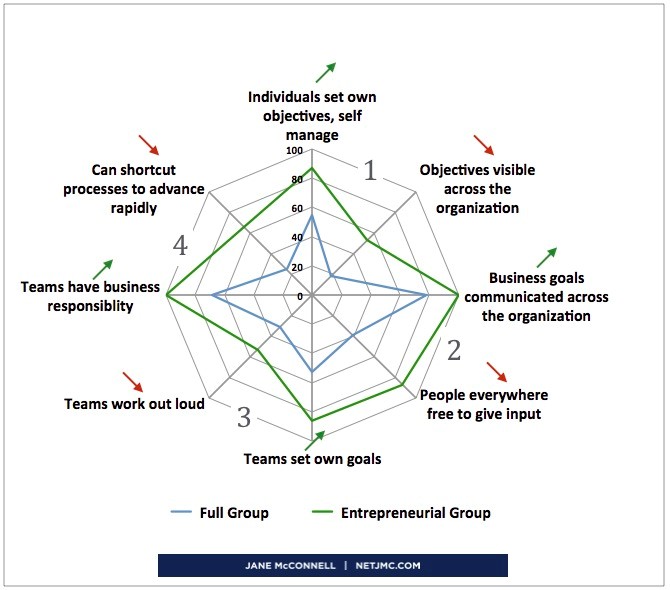

We will look at four pairs of work practices:

Pair 1: Responsibilities of individuals

- Individuals self-manage and self-direct their work as they see best, setting their objectives in 87% of the entrepreneurial sample vs. 55% of the full group.

- People’s objectives are visible across the whole organization (53% vs. 18%).

Pair 2: Transparency of business goals

- Business goals and plans are communicated throughout the organization (100% vs. 78%).

- People are regularly encouraged to give input to business goals and plans (87% vs. 39%).

Pair 3: Team autonomy and visibility

- Teams set their goals and self-manage (86% vs. 53%).

- Teams make their work visible to the larger organization as they work, and before the work is finished. They “work out loud” through continual, ongoing use of internal communication channels (53% vs. 31%).

Pair 4: Responsibility and accountability

- Teams have business responsibility and are accountable for producing actionable output (100% vs. 69%).

- Teams are enabled to act and, when necessary, shortcut enterprise processes to advance rapidly (66% vs. 25%).

The overall impression is that individuals and teams are trusted and accountable. There seems to be broad visibility of activities, including work in progress. A closer look at the four pairs, however, reveals that the first item is specific to the individual or the team; the second relates to its impact in the cross-organizational context. In each pair, the first item is at a much higher percentage than the second item, for both the entrepreneurial group and the full group.

Summarizing the four pairs of practices, we see that individuals can set their objectives, but these objectives are not necessarily always visible across the organization. Business goals may be communicated broadly, but people throughout the organization are less encouraged to give input. Teams can set their goals, but it is rarer for them to work out loud—sharing with the organization as a whole. Teams often have business responsibility and are accountable for producing actionable results, but they are not allowed to shortcut enterprise processes to get faster results.

The full group data has more extreme differences in the four pairs than the entrepreneurial group, where the gaps are smaller. The data that a distinguishing feature in entrepreneurial work cultures is the strength of the cross-organizational context and flows.

Seeding Work Practices

What does this show us about building an entrepreneurial culture? The work practices discussed above have risks and benefits. It is often the second point in our pairs of work practices above — the one that touches the enterprise or cross-organizational dimension—that represents a greater risk as well as a greater benefit. Shortcutting enterprise processes can result in errors and sanctions, or it can accelerate getting a new product to market. Working out loud on a project can result in other people seeing and misinterpreting intermediary project discussions and disagreements, or it can catch the attention of people outside the project who have valuable input to contribute.

An entrepreneurial work culture cannot be created overnight and involves much more than the points covered in this article. However, work practices are a starting point. Like seeds, once planted, they will spread if growing conditions are right. Our entrepreneurial sample suggests that strong, cross-organizational flows are part of a conducive growing environment. The resulting horizontal energy counterbalances the traditional top-down control still common in many places. It helps build a workplace where experimentation and creativity live intelligently alongside risks that are worth taking.

About the author:

Jane McConnell (NetJMC), based in Provence, France, is an independent digital strategy advisor and analyst, who works primarily with large organizations headquartered in Europe. www.netjmc.com. Her latest research will be published in October 2016 in the 10Th annual report: The Organization in the Digital Age. http://www.organization-digital-age.

Thanks. The chart is helpful and I agree with the thrust of the article but one of the most important ingredients is missing, a “value creation playbook.” The playbook explains fundamental value creation concepts and describes best practice value creation processes. See for example, Innovation and Education and other posts at thttp://www.practiceofinnovation.com. Also the book, Innovation: The Five Disciplines for What Customers Want. It describes the value creation playbook that transformed SRI International in Silicon Valley. SRI created HDTV and Siri, among a large number of other world changing innovations.

Thank you, Curtis, for your comment and the link to your site. I’m not familiar with your work but will take a look at it. The intention of the article was to discuss creating overall conducive “entrepreneurial growth” conditions, and was not intended to cover the whole scope of entrepreneurism. It’s such a vast subject. I look forward to discovering your contributions on your site.